"The debate is not about yes to the train or no to the train, but how we look at our lives," a resident of Valladolid, Yucatan.

Photo: Maya Goded/Desinformémonos

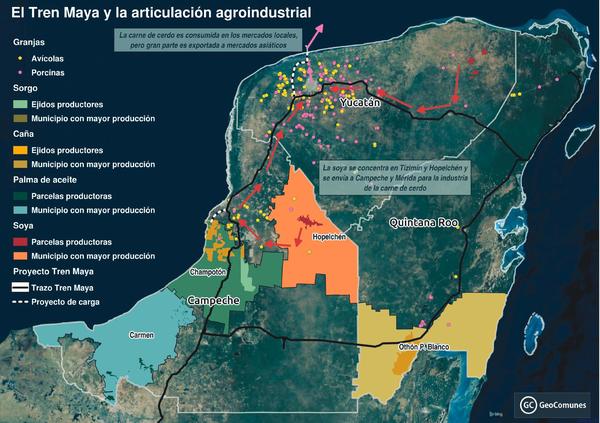

The Mayan Train will kickstart the creation of development hubs in the five states [of Mexico] through which it passes, including industrial parks for meat, fruit, forest products, organic food, and oil palm processing; two train maintenance yards; ecotourism, adventure tourism, and sport fishing; logistical services, food refrigeration, and cargo and fuel terminals; and road and transportation infrastructure with freight hubs, packing facilities, a freight airport at Chichén Itzá, and revitalization of the shrimp industry in Ciudad del Carmen.”1

This deluge of ideas did not come from one of the millions of people who will be affected by the avalanche of projects of all sizes bearing down on the Yucatán Peninsula, which has recently been rediscovered as a potential hub of geopolitical and economic activity. It is, in fact, part of a statement made to the daily Milenio by Rogelio Jiménez Pons, director of Fonatur, the Mexican federal government agency in charge of initiating, administering, and operating the “Mayan Train” project. The project continues to stir up intense debate over its characteristics and possible implications.

Mr. Jiménez said they are planning for the region to become a milkshed (because of its abundant water) and a new home for pork and chicken production facilities, urban markets, food-processing industrial parks, optical fiber networks, and theme-based museums.2

In his initial pronouncements, Mr. Jiménez promoted the Mayan Train as a tourism project consisting of a rail line circling the peninsula and running along existing tracks where possible, although new ones would also be built. It would connect up 18 cities with populations over 50,000 in a region largely inhabited by first peoples. Cities would have zones “for low-income people” who could go to work on foot and also “panhandle as necessary, but on foot.”3 Once built, there would be a total of 30 nodes spread out along the 1452-km route (see map 1).

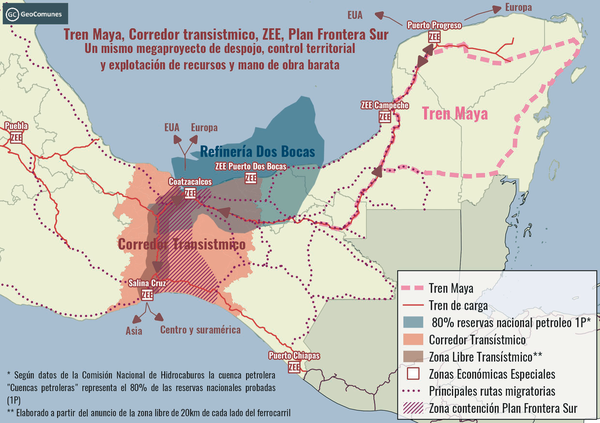

We now know that the proposed Mayan Train is far more than a rail line. It consists of a web of diverse projects, together making up what amounts to a giant “special economic zone.” New hubs for programs, projects, grants, competitive bidding, public policy, and investment will spring up in the five Mexican states involved — Tabasco, Chiapas, Campeche, Yucatán, and Quintana Roo. There has already been land grabbing, deforestation, devastation, poisoning, and environmental degradation, and there will likely be forced population displacement as well. The 181,000-km2 peninsula is being reconfigured as a region of extractive projects, multimodal land and resource monopolization, and maquiladoras. This web will be linked with an infrastructure and transportation corridor crossing the Isthmus of Tehuantepec from the Pacific Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico (an area of 19,997 km2 covering two more states, Oaxaca and Veracruz). The result will be to open up a geopolitically valuable nexus with the United States.

What’s more, the region harbours recently discovered petroleum deposits which, if exploited, would make Mexico the world’s fourth-largest oil producer.4

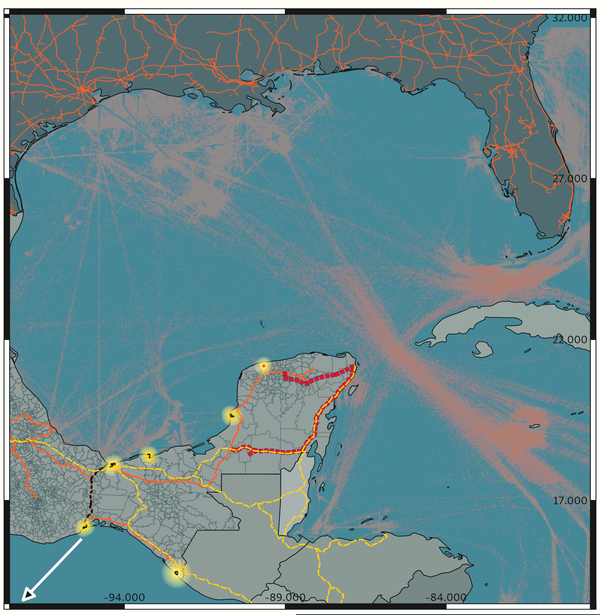

The misnamed “Mayan Train” is a national economic integration and regional redevelopment strategy. It takes advantage of the new North American Free Trade Agreement (CUSMA) to open up a pivotal area on the Yucatán Peninsula and the Isthmus of Tehuantepec across the Gulf of Mexico from the United States. It will turn the gulf into a mare nostrum, providing easy access for US interests to extract resources and impose communications, services, and goods — from industrial products to human trafficking. Access to the Caribbean and northern South America will also be expedited (see maps 2 and 3).

Map 2. The Gulf of Mexico, the Mexican Caribbean, and the Trans-Isthmian Corridor: a geopolitical nexus with the United States. The trajectory of the train corresponds to the one provided by the publication Animal Político. Map by Samuel Rosado.

There has, of course, been a wave of tourism focusing on the important archeological relics of Mayan civilization and on resorts near beaches and jungles. This has already driven people towards a different relationship with nature, with a premium placed on profitmaking by legal and illegal investors to the detriment of fishers, communal land residents, peasants, villagers, and jungle defenders.5

Now, the nation’s rail network will be linked up with goods flows between the Pacific and the Gulf and with the industrial integration of the isthmus, the peninsula, and the Mexican Caribbean. Project design, consulting work, and construction on all manner of projects are being set in motion. There are already 11 wind projects slated for Yucatán, another in Campeche, and a third in Quintana Roo, for a total of 533 turbines. Also on the table are an industrial maquiladora corridor between Mérida and Hunucmá, a “scientific industries' park” modeled after Silicon Valley and numerous “luxury” real estate developments, such as Eknakán and Country Lake (near industrial and high-tech development).6 The project will also extend the belt for entertainment, megatourism, and trafficking (in sex, persons, and drugs) along the east coast of Quintana Roo, from Cancún to Chetumal, including Playa del Carmen and now Puerto Morelos and Bacalar.7

Map 3. Mayan train, transisthmic corridor, ZEE (Special Economic Zones), southern border plan. The same megaproject of dispossession, territorial control and exploitation of resources and cheap labour

Map 3. Mayan train, transisthmic corridor, ZEE (Special Economic Zones), southern border plan. The same megaproject of dispossession, territorial control and exploitation of resources and cheap labourChinese giant Jinko Solar is involved in disputes with Mayan communities in its attempt to build photovoltaic cell parks in Cuncunul and Valladolid. The constitutional challenge (amparo) filed by the communities halted the project (consisting of 313,140 panels over 246 hectares) until early January, when the federal courts cleared the way for it to proceed.8

Lots of money is being spent on pre-construction alone. A sum of $2,360,000 was awarded to Woodhouse Lorente Ludlow for legal advice on various real estate, infrastructure, and energy (solar, wind, etc.) projects; $1,717,000 went to PricewaterhouseCooper, a firm involved in megaprojects around the world, and $1,300,000 went to Steer Davies & Gleave México for technical consulting. Another player in the Mayan Train will be Goldman Sachs, implicated in the US real estate crisis of 2009.9

Much is made of the peninsula’s isolation, underdevelopment, and fragmentation. But in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, henequen, logwood, and mahogany were major exports and the peninsula was linked up with international and domestic markets. Not only did these industries relegate agricultural production to second-class status, but many Mayan labourers were pressed into something like slavery. There was even a nineteenth-century Mayan uprising that went on for many years. The current situation of marginalization and poverty experienced by some communities is a reflection of the gradual, long-term integration of the peninsula into world markets, not a problem of isolation.12

There were special economic zones in southeastern Mexico under previous governments, particularly in the Trans-Isthmian Corridor and the Yucatán Peninsula. When the new government took power, this policy was abandoned as an utter failure.13 Yet a look at the route of the new infrastructure shows the obvious role to be played by the peninsula in a similar scheme — so much so that Mexico’s Business Coordinating Council has expressed the hope that these facilities will be integrated with the inter-oceanic corridor that will be part of the region’s redevelopment. 14

During their existence, the old special economic zones were enclaves with fragmented interconnections to the wider world. The Coatzacoalcos zone was linked to the US rail network through the port of Mobile, Alabama; the Chiapas zone gave access to the Pacific and Central America; the Progreso zone bordered on the Gulf and the Atlantic, and the Tabasco and Campeche zones were designed as outlets to world petroleum markets, pending extraction of Mexico’s newly discovered oil deposits. Since 1997, researcher Andrés Barreda has been predicting an intracoastal canal that would connect the isthmus with northeastern Mexico. It could, he says, become “one of the most important US strategic military routes in the world, a natural extension of the 45,000 km of waterways in the eastern United States.”15 The Salina Cruz port facilities on the Pacific provide an outlet to Asia. And the networking of all these enclaves via rail (the Mayan Train and the Trans-Isthmian Train as an integrated entity) would unify the petroleum, agroindustrial, plastics, tourism, and general goods and services industries. Northwestern Yucatán would become a new Silicon Valley.

The background to the Mayan Train. The Permanent People’s Tribunal that held sessions in Maní, Yucatán in 2013 as part of the Mexican chapter, documented “a much broader process of land grabbing and seizure of the commons, of social, environmental and territorial destruction and of annihilation of social fabrics, which is part of an orchestrated plan to displace populations and empty territories.” It detailed the fight against glyphosate-resistant soybean monocultures, the displacement of traditional farming systems, and the flooding caused by agricultural mechanization. It also denounced extreme deforestation and destruction “of the spaces in which the Mayan peoples can continue to exist and to handle their affairs as they choose, on the basis of self-determination.”16

This synergy of development with surging investment reached a new plane in 2016, when the governors of the three peninsular states signed the so-called Yucatán Peninsula Sustainability Agreement.17 Over fifty companies — including Cemex, Grupo Bimbo, Best Day, Grupo Modelo, Ingeniería y Desarrollo de Yucatán, Universidad Interamericana de Desarrollo, Universidad Tecmilenio, Cuauhtémoc Moctezuma Heineken de México, the Yucatán Development Foundation and the Nature Conservancy, that well-known promoter of corporate control over all conservation efforts — backed the governments of Campeche, Yucatán, and Quintana Roo on this agreement.18

The agreement provides for the coordinated implementation of wind and solar parks; the “sustainable” intensification of industrial greenhouse production; the planting of large areas of agrochemical-dependent oil palm, soybean, and hybrid maize monocultures; environmental services; “the green economy”; carbon credits; factory farms; biosphere reserves, and real estate, tourism, maquiladora, and scientific innovation developments (see map 4).

Map 4. Agroindustrial land use: oil palm, soybean, sugarcane, sorghum, pork and chicken production. It should be noted that there is an increasingly large area in the Bacalar region of Quintana Roo where big acreages of soybean are being planted. In both Hopelchén, Campeche and Bacalar, Quintana Roo, the Mennonite population is the largest grower of agrochemical-dependent soybeans. In addition, this sector leads to forest clearing and harms the production of organic honey for export, which Mayan peasants have worked years to build up. See: www.geocomunes.org

The Mayan Indigenous Regional Council of Bacalar stated: “The ‘sustainability’ put forward by these governments is very different from the kind we practice; they are trying to help the corporations, even at the cost of forest devastation, as occurs with ‘renewable’ energy. Photovoltaic cell parks necessitate the deforestation of thousands of hectares, which will be done with the governments’ permission.”19

But the corporations are not getting a free pass. For one thing, several constitutional challenges filed by members of communities in Yucatán and Quintana Roo against the agreement have succeeded in court. In one of these cases, the second district judge of Yucatán recognized the legitimate interest of the Mayan population, which must be treated with “equality and not discrimination.” He acknowledged and valued the presence of the Mayan communities and their economic, political, and religious transcendence, as well as their historical occupation of the Yucatán Peninsula. This means, the judge wrote, that “an effective consultation” will be necessary. In so doing, he set a precedent for durable government recognition of the Mayan people on their territory.20 In the wake of the government’s consultation on the Mayan Train, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights in Mexico pointed out that this consultation did not meet international standards and was not approved by the communities.21 The people’s organizations accused the government of a sham process.

Even if the judge’s decision is forgotten, it reflects an underlying fact that will continue to carry weight, although some may choose to ignore it: that the peninsula and the isthmus are the largest contiguous territory where the Mayan language is spoken and where the traditions, struggle, and resistance of the Mayan peoples carry on, alongside those of other, equally combative first peoples. The Mexican government is obligated to respect the right to self-determination asserted by the people’s organizations of the isthmus and the Zapatista communities. The Mayan peoples’ historical presence here, and their continued importance to the preservation of biodiversity and cultural continuity in southeastern Mexico, are incontrovertible facts. And they have left no doubt as to their commitment to this struggle, and their willingness to devote their lives to it. A struggle that joins a larger one across Latin American to defend land and territory against megaprojects.22

Thanks to Samuel Rosado for research, analysis, and drawing of maps.

Thanks to GeoComunes for permission to publish its maps.

We thank Muuch' Xiinbal' and the Regional Indigenous Mayan Council of Bacalar, defenders of the territories of the Mayan people, for their comprehensive approach.

You are invited to visit the websites of our comrades who are also active in this struggle: https://hablanlospueblos.org/Tren_Maya.html and https://desinformemonos.org/

https://hablanlospueblos.org/TM/impactos-sociales-y-territoriales-del-tren-maya.-miradas-multidisciplinarias/index.html

https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/estados/Asur-participara-en-Tren-Maya-Jimenez-Pons-20181021-0075.html

http://www.ccpy.gob.mx/archivos/documentos-agendas/tmp_201801165327.pdf

19. Press release on the final judgment in the ASPY caso in Quintana Roo, https://educe.org.mx/?p=661

20. Second District Court of Yucatán, decision on constitutional challenge (amparo) 83/2017 VIA, granting the complainants protection from the Acuerdo General de Coordinación para la Sustentabilidad de la Península de Yucatán (ASPY), 20 October 2017.

21. “El proceso de consulta indígena sobre el Tren Maya no ha cumplido con todos los estándares internacionales de derechos humanos en la materia”, www.hchr.org.mx see Magdalena Gómez, Resistencia indígena ante el despojo, La Jornada, 24 de diciembre, 2019 https://www.jornada.com.mx/2019/12/24/opinion/012a2pol

22. Gloria Muñoz Ramírez, Derecho de réplica, hablan los pueblos.org, desinformémonos.org, September 2019, remarks by the CCRI-CG of the EZLN on the 26th anniversary, 3 December 2019.